In late July I went out to the nomad grasslands of eastern Tibet with the intentions of finishing off a portrait series I’d been working on for a while. I’d wanted to walk away with around eight shots that I’d been envisioning for a while – some of the shots I’d been thinking about (read: obsessing about) for over a year. Once the weekend was over and everything was said and done I walked away with only two shots that I liked and were worth adding to the collection.

I didn’t really get what I wanted – but that’s ok.

Managing expectations

Planning ahead is good. Knowing what you want and how you are going to get it before the camera is in your hands creates the kind of situation that turns good shots into great shots. Bridging the ‘creative gap’ is most often accomplished with significant forethought. It’s important. I know photographers who have stacks of notebooks filled with shot diagrams for shots they have yet to take.

There’s a problem though. When going to a new place or entering a new culture, what happens when we envision shots that don’t exist? The camera in our brain is often bigger than the one we hold in our hands – that camera being limited by physics, time, space, and reality while the one in our head is allowed to roam free and conjure up endless amounts of images. This can create a huge gap that, if not recognized, can eventually lead to frustration.

Let me make it abundantly clear – a good imagination is absolutely necessary and blurring the lines between reality and non-reality is so important as a creative. Some of the best pictures I’ve ever seen are achieved when a photographer goes to great lengths to bridge what they see in their head with what they can actually produce. Having that kind of imagination is obviously important, no one is debating that.

But what happens when the creative gap is too large and unrealistic? For example I’m not going to find Tibetan Nomad with a 52’ TV playing Halo 3 on the grasslands no matter how much I want to visually highlight the juxtaposition between the modern and the ancient. That shot doesn’t exist and unless I’m willing to go great lengths to create a shot that isn’t at all accurate I’m just not going to get it. This kind of unrealistic creative gap can lead to a frustrated photographer and if pushed far enough, a bunch of offended locals.

Research, Flexibility, & the concept of Pre-disapointment

So how do we create realistic expectations in travel photography? One of the best ways to manage expectations is to do as much research as possible. Read about the people, place, and culture you are going to visit before you visit it. Talk to people who have been there. The more research the better. Research has the capacity to help us prepare for the unknown and adjust our shot lists to fit what is feasible.

Secondly, it’s obviously important to be flexible. If we aren’t flexible, we often start to force situations and end up with crappy results, pissed of locals, and a can quickly become frustrated. A frustrated photographer hardly ever produces good, let alone great shots. Flexibility gurantees us the ability to think outside of whatever box we might have built for ourself and continue to function as a professional. Opportunities most often present themselves to those who are flexible.

Lastly, I want to introduce the concept of pre-disappointment. As depressing as the idea sounds, it’s simply this – a mental realization that what we envision about a people, place, or culture before we visit it will rarely ever match up with what is true about the place. Even with extensive research, the gap between real and imaginary can remain significant. In fact, research without the concept of pre-disappointment can exsaserbate disapointment if research and reality don’t match up. We must be mentally prepared to encounter something that is completely ‘other’ than what we expected, assess the opportunities, and move forward. In short, pre-disappointment is that concept that, even with research, our imaginations will wonder away from reality and that we need to always be ready to be flexible with what we previously thought about something, even if we researched the heck out of it.

Don’t miss the forest through the trees

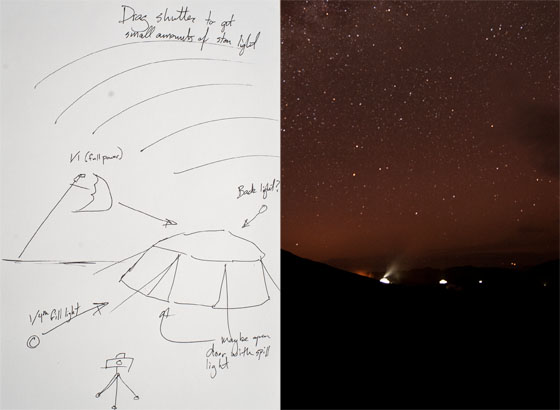

On a trip a few months ago I had one shot that I’d been planning for over a year. I’d envisioned the shot before on previous trips but didn’t have the tools or the time required to pull it off. I wanted to take a picture of a nomad yak wool tent lit with speed lights from both the front and rear and then keep the shutter open long enough to get the stars streaking through the sky – all on an expansive and endless grassland. Sounds awesome, doesn’t it? I had diagramed it out and knew exactly how I was going to execute it.

This last time when I went out I couldn’t find a single black yak wool tent and the scene which I’d been envisioning simply didn’t manifest itself. I tried to get a version of the shot but it just wasn’t working. Lots of things weren’t going right (like, being chased by away by tibetan dogs + no strobes) You can see the embarassing ‘result’ below – decidedly not good and not what I was after.

The point is that we shouldn’t overly obsessed about one shot – if it’s not realistic – so much so that we miss other great shots. I obsess about shots all the time, but is it healthy to do so if the shot isn’t remotely realistic at the time and miss out on other shots? If it’s not working, pull back, regroup and go shoot something else. Don’t miss out on other great shots chasing a shot that may not present itself or will be a crappy ‘version‘ of your vision. The opportunity to capture the shot will still exist – the vision doesn’t die with one or two tries. I would suggest that the vision actually gets refined and made better with a few missed opportunities I still want this shot – I can still see it in my head as clearly as if it were hanging on my wall.

Thanks for posting this, Brian. It’s encouraging.

Sound advice Ray